World War II bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki stunned the world with the destructive capability of atomic weapons. Even so, the power of the atom also impressed scientists and government personnel. Perhaps it could be harnessed for productive peacetime activities. Operation Plowshare was the result of that idea. The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) program, instituted by the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, was established in June 1957, taking its name from the Bible (Isaiah 2:4): “…they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore.”

Ambitious plans were made to employ nuclear explosives for such projects as widening the Panama Canal, constructing a new sea-level waterway through Nicaragua, cutting paths through mountainous areas for highways, and connecting inland river systems. From the program’s start until 1973, 31 nuclear warheads were detonated in 27 separate tests.

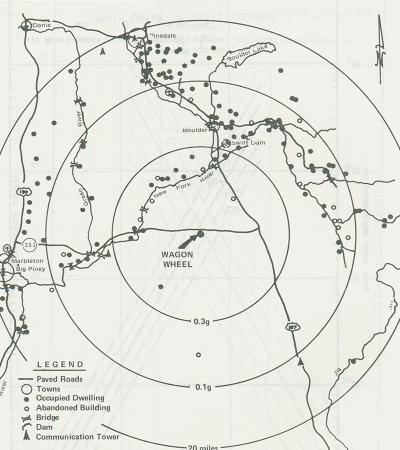

In the 1960s, the AEC approved nuclear detonations in the West to help extract natural gas. From 1967 to 1973, three experiments were conducted in New Mexico and Colorado in partnership with the El Paso Natural Gas Company (El Paso). In 1968, El Paso signed a contract with the AEC to do the same in Wyoming cattle ranching country– Sublette County –on Bureau of Land Management property leased to El Paso. Known as Project Wagon Wheel, it was to study the effectiveness of nuclear power to break up sandstone in this area to release an estimated 300 trillion cubic feet of natural gas at depths between 10,000 and 18,000 feet.

Initial expectations ran high in the Sublette County towns of Pinedale, Big Piney and Boulder. One local newspaper exclaimed excitedly in January 1968 that Pinedale might become the natural gas center of the United States. But when the draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) was made finally public in January 1972 revealing that El Paso planned to detonate five 100-kiloton devices underground a few minutes apart, residents began to worry publicly about the likely effects of the explosions and fallout. Three billion cubic feet of radioactive gas would be released and flared—burned off—during the test, leaving radioactive tritium, krypton-85, and argon-37 in the local atmosphere. There was no mention of impact on cattle and wildlife and on feed for these animals in the area surrounding the test site. AEC maintained that the unavoidable radiation levels would be very low and of no danger. However, the Wyoming Game and Fish Commission released a scathing comment regarding the inadequacies of the draft EIS on fish and wildlife.

A group of local ranchers, housewives, business and professional men and women, teachers, and students formed the Wagon Wheel Information Committee (WWIC) to educate themselves about the proposed atomic test. In March 1972, the WWIC convened a public discussion about the project at Pinedale High School. More than 600 people came to hear the panel of state, county, and local officials. No one from the AEC or El Paso were on hand. AEC and El Paso representatives finally went before the public in late April, at a meeting convened by the Wyoming Wildlife Federation and the Green River Valley Cattlemen’s Association. The meeting ran five hours and, again, attendance was high. Phillip Randolph of El Paso told the crowd there was “little potential danger” in the plan.

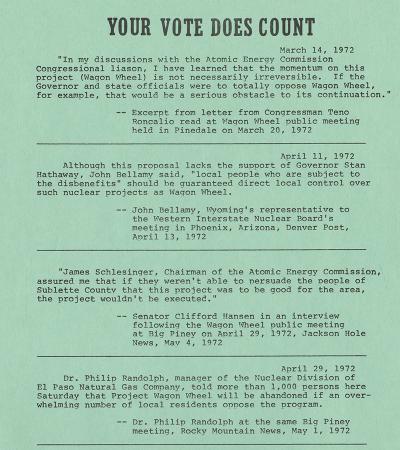

There were some supporters in Sublette County for Project Wagon Wheel. A bank president in Big Piney declared that the endeavor project could help the local economy and the AEC should be trusted. Wyoming Governor Stan Hathaway also favored the proposal, but as public opposition mounted throughout 1972, the governor lessened his public support somewhat and called for more study and information about the atomic test.

The WWIC published its official comments on the draft EIS and sent them to the AEC, which had stated that comments would be welcomed and considered. However, WWIC comments were never officially answered nor included in the Final Environmental Statement that was released in September 1972. Wyoming’s Democratic senator, Gale McGee, told the Casper Star-Tribune that the report “was premature” and “failed to cover the overall impact.”

News about the project began spreading beyond Wyoming’s border through the efforts of the WWIC. Newspapers across the nation published articles reflecting more sympathy for Sublette County residents than for El Paso and the AEC. Opposition focused on groundwater, fish and wildlife, costs to taxpayers, need for alternative energy sources, seismic activity and lack of public hearings.

To gauge local support for the project, the WWIC decided to hold an unofficial “straw poll.” Because Wyoming statutes prohibit votes on public policy, the issue could not be put on an official ballot. The poll was conducted Nov. 7, 1972, the day of the presidential election. Results were overwhelmingly against the project, with 970 opposed, 279 in favor, and 105 undecided. El Paso had assured residents that if they did not want the project to occur, it would not. The company’s response to the straw poll was to say the vote was “premature” because they were only considering the project. Philip Randolph of El Paso was asked at a subsequent news conference why there was a 19,000-foot hole if the project was only being considered. Furthermore, what non-project had El Paso and the AEC spent $8 million and issued two environmental impact statements for?

The WWIC began contacting the Wyoming congressional delegation in an effort to get Project Wagon Wheel cancelled. U.S. Sen. Cliff Hansen set up a meeting in Washington, D.C. in February 1973 between the WWIC and AEC Director Dr. James R. Schlesinger and other officials involved with the project. However, WWIC members learned upon arrival that Schlesinger refused to come to a meeting. Instead they met with Environmental Protection Agency officials, staff scientists, and with Department of the Interior representatives who told them the Bureau of Land Management could not stop the project. While in Washington, D.C., WWIC Chairman and Boulder rancher Floyd Bousman appeared on the Today Show opposite Randolph of El Paso to discuss the Wagon Wheel Project.

Meanwhile Wyoming’s lone congressman, Democrat Teno Roncalio, was appointed to Congress’s Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, where he worked steadily, and often with economic arguments, to de-fund the Plowshare Program. (Those arguments were not hard to make. The Rulison Project, for example, had produced $1.4 million worth of natural gas but cost the ACEC $11 million, the High County News reported in March 1973.) Senator Cliff Hansen noted that President Nixon’s budget provided no funds for Project Wagon Wheel until 1977 at the earliest.

In 1974, the test well that El Paso had drilled was used instead for an attempt at what then was called massive hydraulic fracturing, to crack open the gas-bearing rock by pumping large amounts of water under pressure down the well. The procedure did not work, and the hole was eventually plugged and never reopened. A nuclear detonation never occurred in Sublette County. Project Wagon Wheel was never cancelled; it just was never funded. Because the project was not cancelled, the WWIC did not disband until 2006.