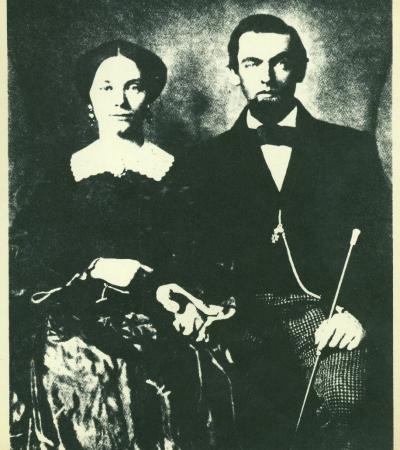

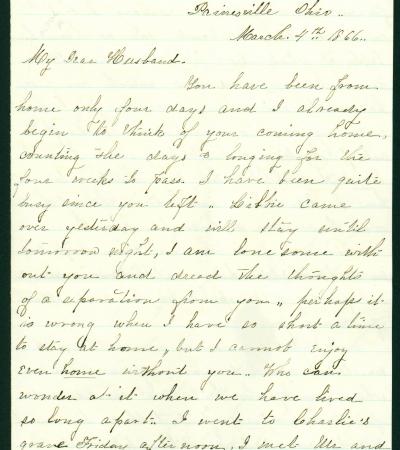

Brigadier General John S. “Jack” Casement (1829-1909) had already served honorably in the Civil War by the time he became a tracklaying contractor during the building of the transcontinental railroad. Working for the Union Pacific Railroad Company, it was Jack’s job, along with his brother and business partner Dan Casement, to build most of a rail line that spanned 1,776 miles from Omaha, Nebraska, to the meeting point with the Central Pacific rail line at Promontory Point, Utah. Until the Casement brothers took on the work, the Union Pacific had made only slight progress since breaking ground in December 1863. When Jack was hired in early 1866, he applied his existing railroading expertise as well as military skills and discipline to the work. Dan (1834-1881) was responsible for financial operations, which at times required him to dip into his own pocket to meet expenses. To make money on the side, Jack took grading work and opened general stores in towns along the route. Under the Casements, the work was completed in record time on May 10, 1869. Jack was a married man with a young family during his years with the Union Pacific. In 1857, Jack had married Frances Marion Jennings (1840-1928), an educated young woman from Painesville, Ohio. The couple wrote many letters to each other while Jack was away. The letters illustrate the experiences of a "railroad widow" and her driven, yet loving husband. Also included in the correspondence presented here are letters Jack received as a Union Pacific employee. Additionally, there are letters Jack received after being elected in 1867 to be Wyoming Territory’s first Representative in Congress. Ultimately, Congress ruled the election as illegal, and Casement was never seated. After completion of the transcontinental railroad Jack continued to be active in railway work and Frances became a renowned suffragette.

Additional content for this collection can be found in the "Inventory for collection.”

Copy of wedding photograph of John S. and Frances Jennings Casement, October 14, 1857.

Due to her family's wealth, Frances received a formal education at the Painesville District School in Ohio, a rarity for children during this time. She later graduated from Painesville Academy in 1852 and attended Willoughby Female Seminary in 1855-56. Jack Casement met Frances, who was called "Frank" while he was working as a railroad contractor in Ohio. Shortly after completing her studies, Frances married Jack.

One of John S. and Frances Jennings Casement's sons. Photograph by F. Clapsadel of Painesville, Ohio

The couple had three sons: Charles J. (b. 1861), John Frank (b. 1866), and Dan Dillon (b. 1868). Charles died at age 4 and John at age 19.

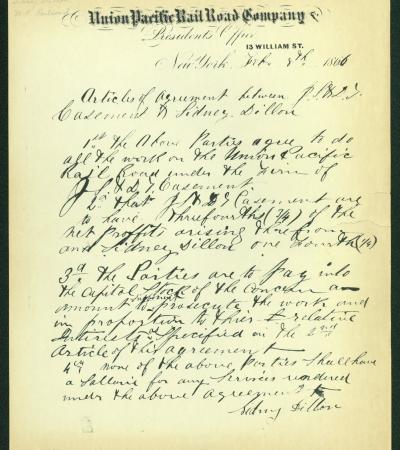

Copy of the articles of agreement between J.S. & D.T. Casement and Sidney Dillon, February 8, 1866.

Realizing the importance of increasing production, Union Pacific's first vice president and general manager, Thomas C. "Doc" Durant hired General Jack Casement as the Union Pacific's construction boss. Casement brings military discipline and mass organization to the rail line. Sidney Dillon was one of the principal contractors for the Union Pacific during the building of the transcontinental railroad. For more information about the contract, see Union Pacific Agreement -

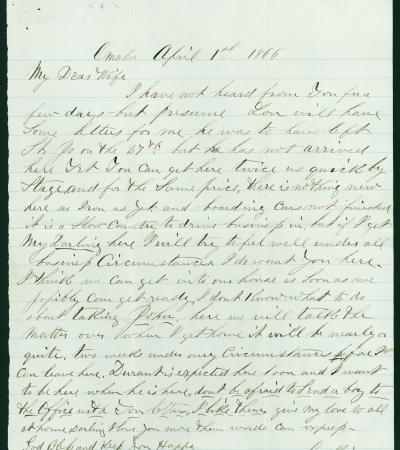

March 1866

Jack Casement had spent the winter at Omaha preparing the ingenious box cars he used during the coming years. They were built atop Union Pacific undercarriages. The box cars served as bunkhouse, kitchen, dining hall, office, pantry, and supply depot. Each had a small arsenal in anticipation of trouble from Plains Indians. He had workers lined up (many of whom were former military personal) and was anxious to work. But the iron rails had to be delivered by paddle steamers on the Missouri River, and the river was frozen for most of the month of March.

April 1866

Even though he has plenty of workers, the receipt of just a few iron rails yet and uncompleted boarding cars largely hold up Jack in his work. In May, Thomas Durant hires General Grenville Dodge to be chief engineer of the Union Pacific. That summer Casement crews add 60 miles of track to bring the Union Pacific line to the 100 mile mark, thus guaranteeing UP the irrevocable right to continue westward, as stipulated in the Pacific Railroad Act.

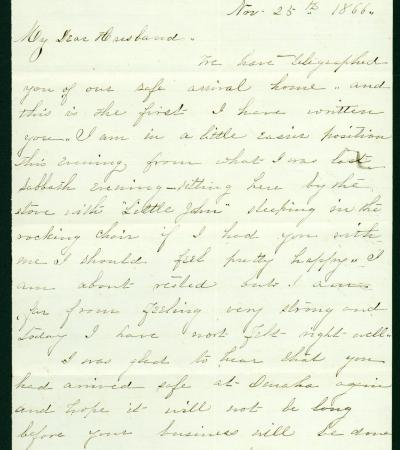

November 1866

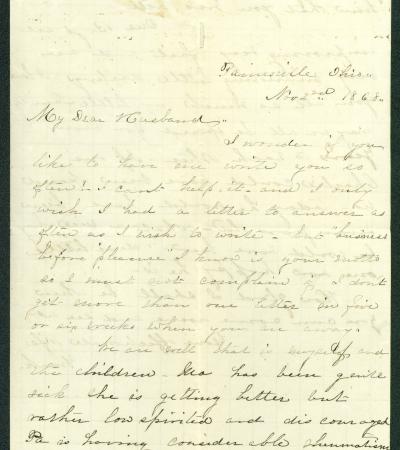

On September 29, the Casement's son John Frank was born. In October, Casement and his crews passed the 100th Meridian line on the Nebraska prairie. Jack's family arrive home in Painesville in mid-November having spent some months in Omaha to be closer to him. Frances encourages Jack to come home to Painesville more often to help raise their son, a plea she would repeat over the years.

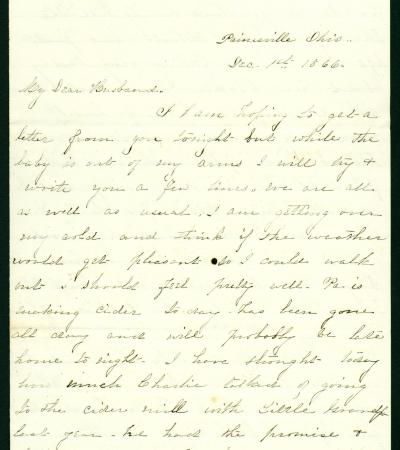

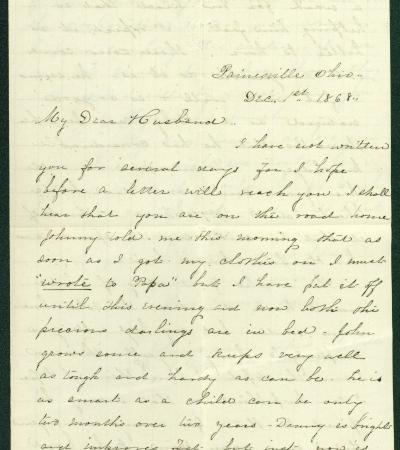

December 1866

While Frances writes of her loneliness, their family, and visitors, Jack is focused on work. He and his crews lay track until mid-December while also preparing winter quarters in North Platte, Nebraska. The town becomes "Hell on Wheels" when saloons, prostitutes, and criminals arrive to profit from the crews . Jack doesn't leave for home until Christmas Eve.

January 1867

Jack returned to Omaha where UP contractor Sidney Dillon asked him to remain for a few days. Jack reported of others staying at the hotel including UP lead surveyor and construction engineer Samuel Reed and his wife as well as a Mr/Mr. McCormick and a Mr/Mrs Bruce. Creighton and Stuger are also mentioned. Jack may be referring to prominent Omaha businessman Edward Creighton.

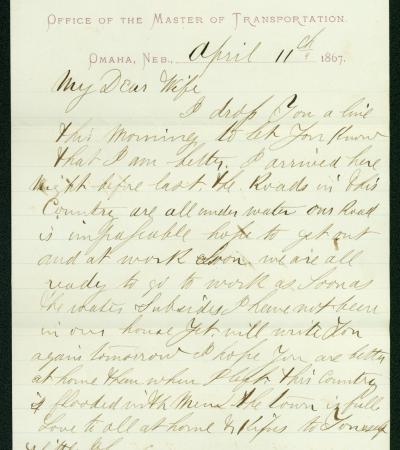

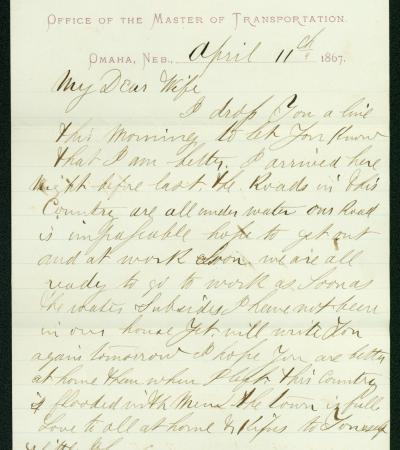

April 1867

Work of the railroad crews is stymied in mid-April due to water on the road, making it impassable.

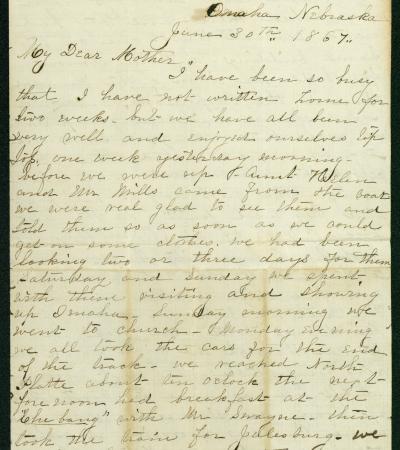

June 1867

Frances writes to her mother from Omaha of their train trip to the end of the tracks. She includes a short description of the new town of Julesburg, Colorado, which served briefly as an end of tracks town. She reports that Jack left with a large group for the Black Hills in Wyoming, possibly to scout out the next section of work.

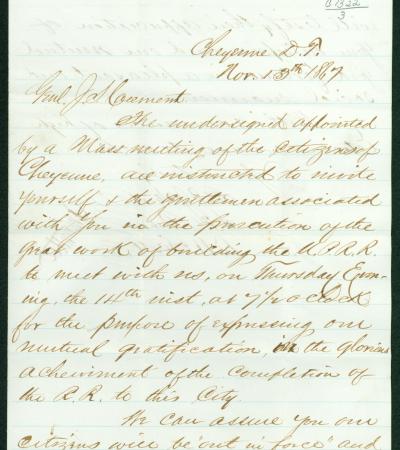

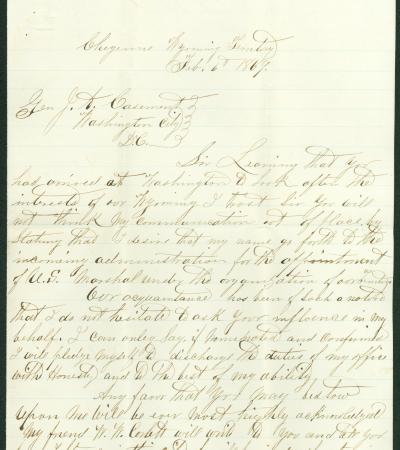

Letter to J. S. Casement from prominent men of Cheyenne, Dakota Territory, November 13, 1867

UP platted the townsite of “Crow Creek Crossing” on July 5, 1867, which became the town of Cheyenne, Dakota Territory, on August 8. The tracks reached the new town on November 13, 1867, with the first train arriving the following day. Cheyenne grew so quickly it was dubbed the “Magic City of the Plains.” Excited Cheyenne citizens held a celebration with Jack Casement as their honored guest.

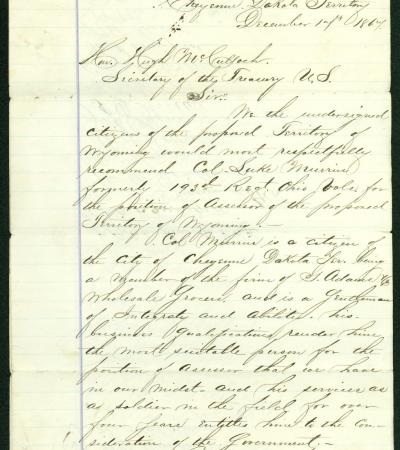

Letter from Cheyenne citizens to Hugh McCulloch, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, December 17, 1867

Jack Casement was such a popular figure that he was elected as Wyoming's first Representative in Congress. After a long struggle, Congress ruled that the election was illegal and Casement was never seated. Here Casement forwards a letter from Cheyenne citizens requesting that Luke Murrin be recommended as Assessor for the proposed Territory of Wyoming. Murrin went on to serve as Cheyenne's second mayor beginning in January 1868.

January 1868

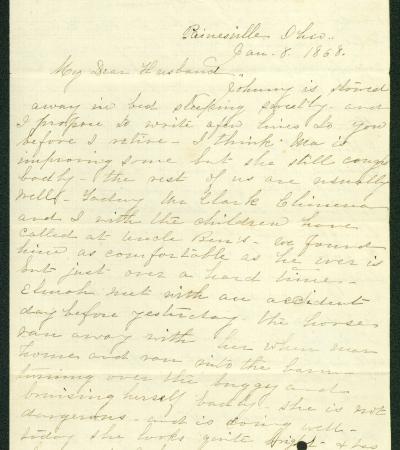

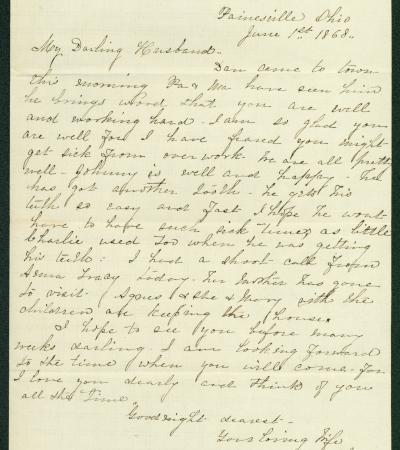

Frances is home in Painesville and writes to Jack of happenings among friends and family. She asks him to write her about his "doings and Washington affairs."

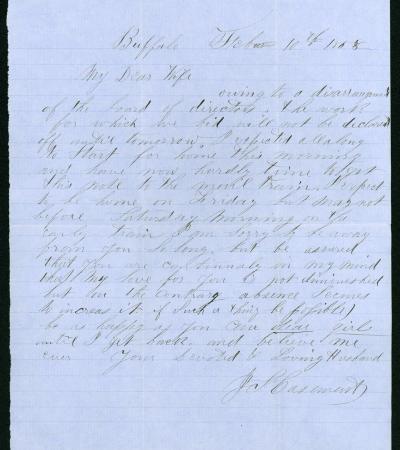

February 1868

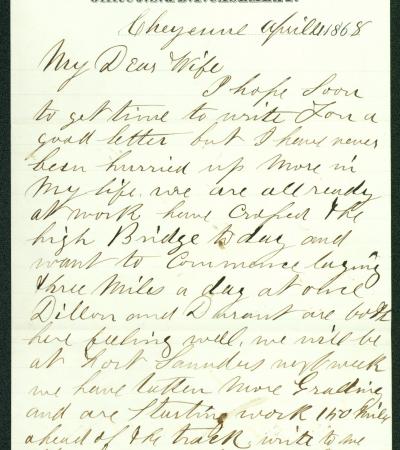

April 1868

Jack notes how busy he is and, indeed, his crews had recently completed the Dale Creek Bridge, located about 20 miles southeast of Laramie. The bridge presented UP with one of its greatest engineering challenges. Casement remarks that the grading crews will be working west of Fort Sanders and expresses confidence that his crews can lay more than three miles of track per day, possibly reaching Salt Lake City that year.

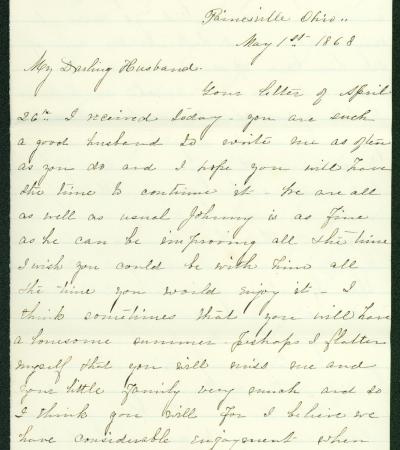

May 1868

Frances writes that she should stay in Painesville this summer; although not stated, she is expecting the couple's third child. She expresses gentle frustration over Jack's time away, including his work as a Wyoming representative. Attacks on the railroad by Native American tribes come up again. Jack describes the busy progress of the rails, explaining baking must be done night and day due to the number of workers. Although not mentioned, the rails reached Laramie on May 4.

June 1868

Jack's letters are infrequent as he stays busy with the railroad and Wyoming matters, including the organization of Wyoming as a territory. Frances comments on the ill health of their son John Frank.

July 1868

Jack receives a letter from a Chicago man saying that men there are looking for railroad work. Constituents of the proposed Territory of Wyoming write Casement (their as yet unseated representative) regarding a man they recommend for U.S. District Attorney. On July 25, the Territory of Wyoming was established. H.M. Slade writes to Casement of his desire to be named Secretary of Wyoming Territory. The Casement's third child, Dan Dillon, was born July 13. Before the end of the month, Jack was back at work on the railroad.

August 1868

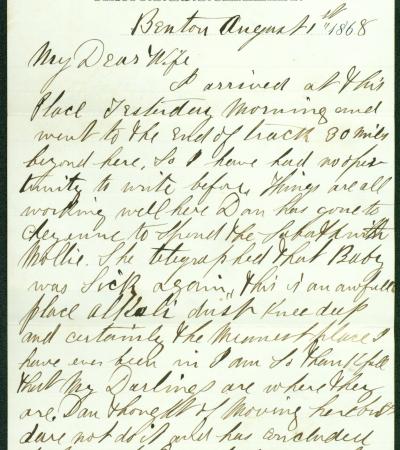

Jack expresses his disgust with Benton, Wyoming Territory, which was one of the end-of-track "Hell on Wheels" towns. He also writes of troubles with stock animals dying due to overwork. By mid-month, track laying was going well, although Jack complains of a "great nuisance" of excursionists. Jack receives two more letters, this time from Michigan and New York, of men who would like to work for the railroad. Frances writes of family and friends is still recovering from childbirth.

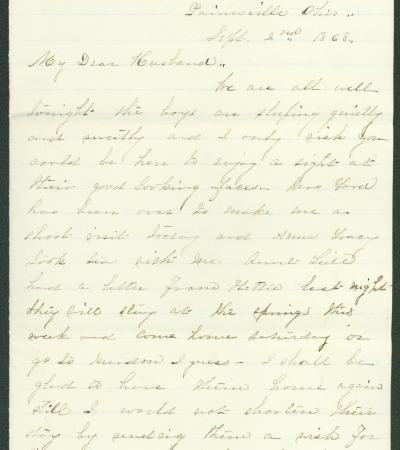

September 1868

Frances gently chides Jack over their long separations. By mid-month she expresses concern that she is not receiving letters from him. Jacks explains that he constantly has visitors to deal with. A man responds to the Casement's call for 100 more men.

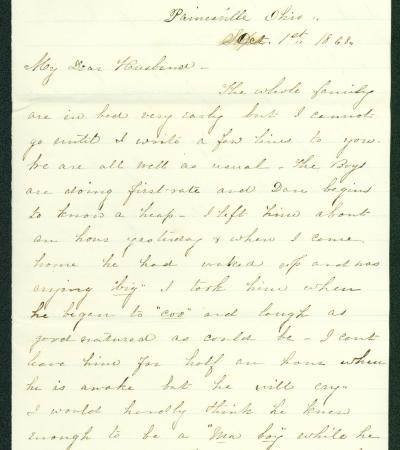

October 1868

The rails reached Green River, Wyoming Territory, on Oct. 1, 1868. Jack makes a very short visit to Painesville in early Oct. Frances writes that Dan Casement's wife Mary (also known as Mollie) is still unwell. Frances is upset that not only did Jack appear to forget their wedding anniversary on Oct. 15, but she has only received one letter in four weeks. Jack explains that someone is always visiting his tent or he is on the move. He notes that Thomas Durant is there and, while trying to hurry things up, is only creating delays.

November 1868

Jack's niece Emily Hull asks him to assist her with her medical bills. Jack mentions that supply delays are hampering UP's plans to make it to Salt Lake City before heavy snows fall. He notes that Native American attacks are happening east of his location in Granger, Wyoming Territory.

December 1868

A letter from Frances on December 1 remarks on the death of their son Charlie three years ago. Jack may have returned home soon after as that is the only piece of correspondence between them.

February 1869

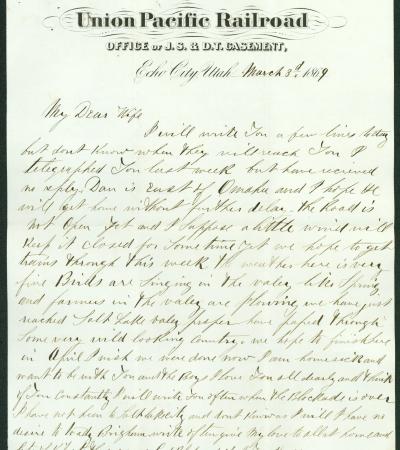

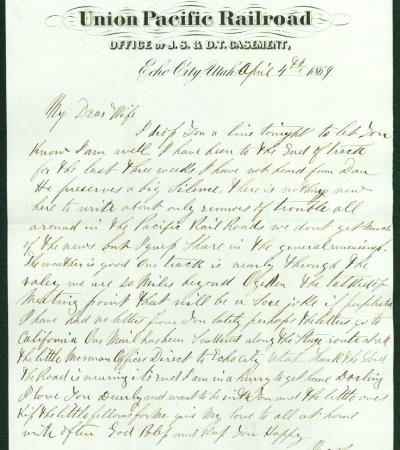

As Wyoming's congressional delegate, Jack receives a letter from a man asking for a recommendation to be U.S. Marshal for the new Territory of Wyoming. Jack writes to Frances from the terminus of Echo City, Utah, of the UP's dire financial situation.

March 1869

Jack remarks early in the month that the railroad is still blocked by snow to the east, but his crews have reached Salt Lake Valley to the west. Supply problems threaten to delay completion. He has collected some money UP owes him. Jack remarks that he is not keen to meet Brigham Young.

April 1869

Jack continues to write from Echo City, Utah. He notes there are rumors of trouble about the Pacific Railroad. A great rivalry existed between the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads.

May 1869

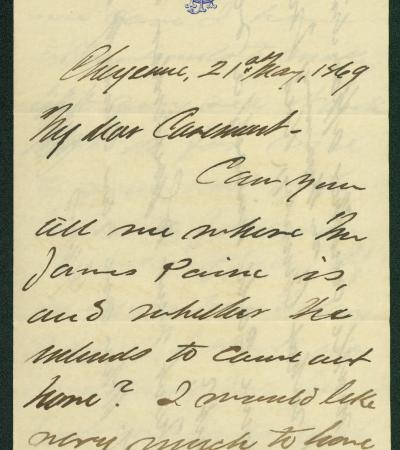

Wyoming Territory Governor John A. Campbell writes to Jack of his search for a man named James Paine. In late May Sidney Dillon requests Jack's presence in New York and urges hims to finish affairs as soon as possible.

Letter to Oliver Ames from W. Snyder, October 2, 1869

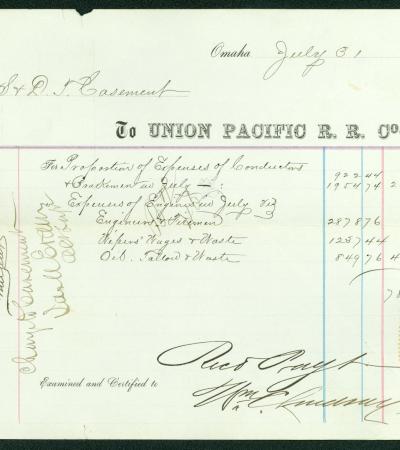

Despite having received millions of dollars in government funding, shady bookkeeping bankrupted the UPRR and the company found itself unable to pay its bills. The Casement brothers were caught up in this issue when payment was due to them.

Invoices submitted to the U.P.R.R. by the Casement brothers, July through December 1868

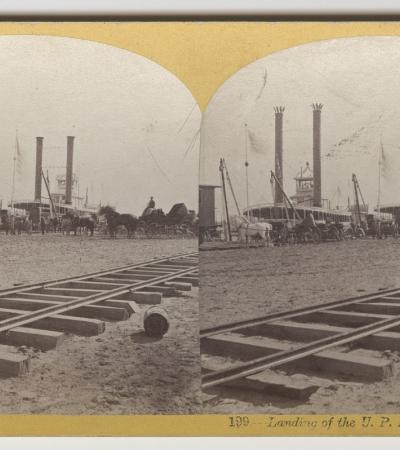

"199. Landing of the U.P.R.R. Excursts. at Omaha (2)," photograph by John Carbutt

John Carbutt (1832-1905), a publisher and printer of stereo cards in Chicago, briefly preceded Andrew J. Russell in working for UP; however, Carbutt’s work for UP was more limited in scope. He was hired to document a promotional event celebrating the company’s progress: the October 1866 Union Pacific Excursion to the 100th Meridian. UP had completed almost 250 miles of rail nearly a year ahead of schedule to reach that point.

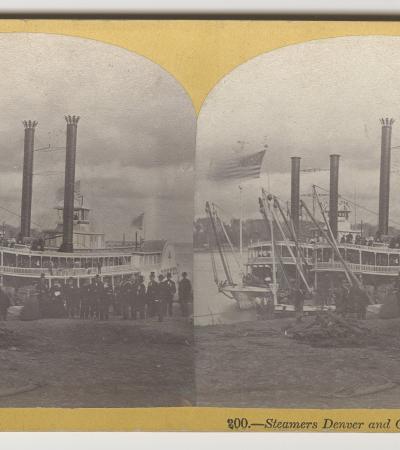

"200. Steamers Denver and Colorado, U.P.R.R.," photograph by John Carbutt

Photos labeled "Union Pacific Rail Road, Excursion to the 100th Meridian, October 1866.

"207. Excur. Party 275 ms. W. of Omaha, Oct. 24 '66 (2)," photograph by John Carbutt

The 100th meridian is often considered a rough border between the western and eastern United States.

"208. Westward, the Monarch Capital Makes its way," photograph by John Carbutt

Thomas Durant

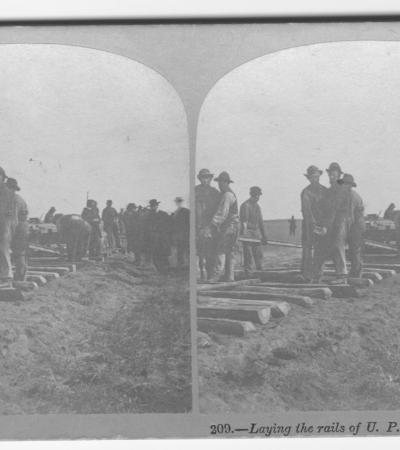

"209. Laying the rails of U.P.R.R. - two miles a-day," photograph by John Carbutt

The excursionists had trouble catching up with the construction crews, who were laying track at an incredible rate of almost two miles a day. They finally met them some 40 miles past the 100th meridian, and celebrated with another lavish meal and an hour-long fireworks show.

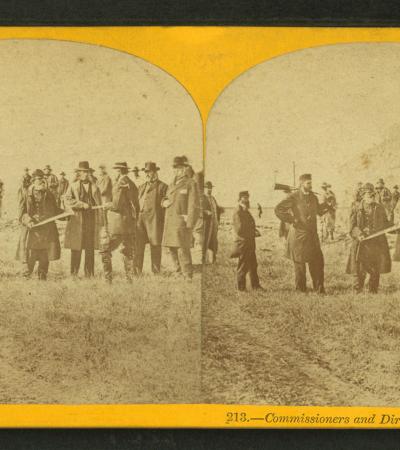

"213. Commissioners and Directors of the U.P.R.R.," photograph by John Carbutt

Photos labeled "Union Pacific Rail Road, Excursion to the 100th Meridian, October 1866."

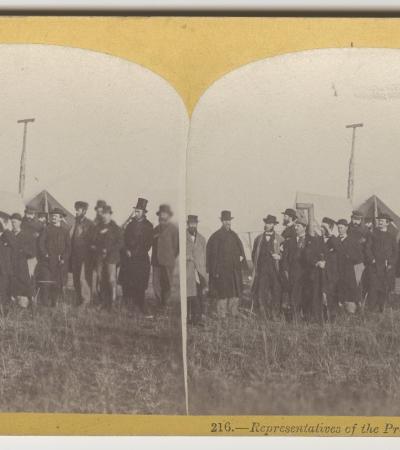

"216. Representatives of the Press, with the Excursion," photograph by John Carbutt

Thomas Durant made sure to let the world hear about the event by inviting reporters from the major newspapers.

"217. The Boys that made us comfortable, All Hail," photograph by John Carbutt

Photos labeled "Union Pacific Rail Road. Excursion to the 100th Meridian, October 1866."

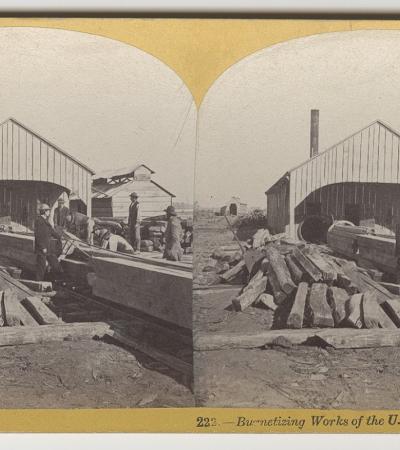

"222. Burnetizing [sic] Works of the U.P.R.R. at Omaha (1)," photograph by John Carbutt

The Burnettizing works were constructed in 1865. The plant treated mainly cottonwood ties under pressure with zinc chloride. This method is called Burnettizing, after its 1838 inventor, William Burnett. However, problems began right from the start. The handcut ties were too large and the zinc chloride solution was too strong, which resulted in brittle ties. This was a common problem with early Burnettizing. Also, the plant was not big enough to handle the vast numbers of ties used in the rapid construction of the transcontinental railroad.

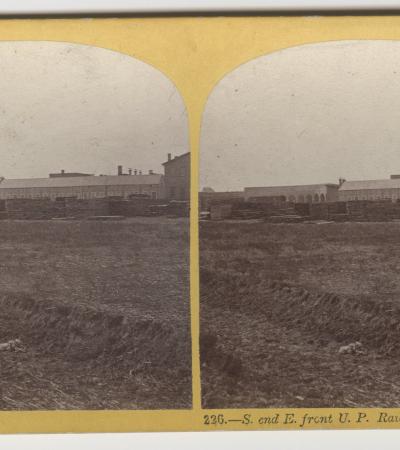

"226. S. end and E. front U. P. Railroads Works at Omaha," photograph by John Carbutt

Photos labeled "Union Pacific Rail Road, Excursion to the 100th Meridian, October 1866."

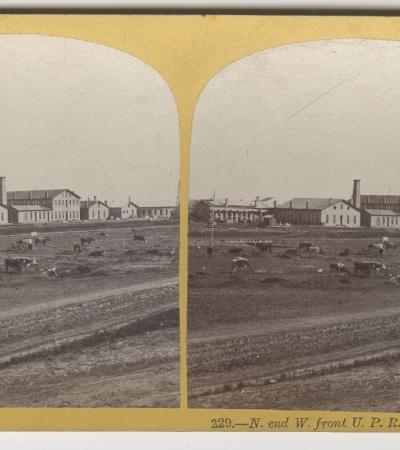

"229. N. end and W. front U.P.R.R. Works, Omaha," photograph by John Carbutt

Upon landing in Omaha, the excursionists were up at an early hour ato visit the Union Pacific's extensive depots and machine shops.

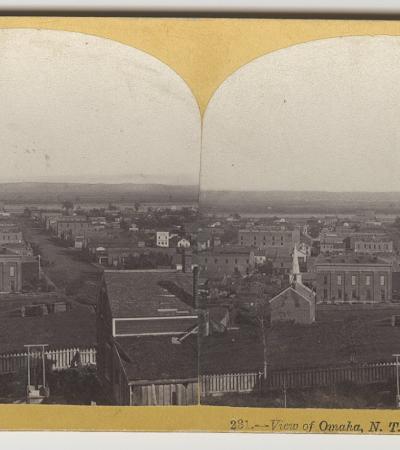

"231. View of Omaha, N.T. from Capitol Hill (2)," photograph by John Carbutt

Photos labeled "Union Pacific Rail Road, Excursion to the 100th Meridian, October 1866."

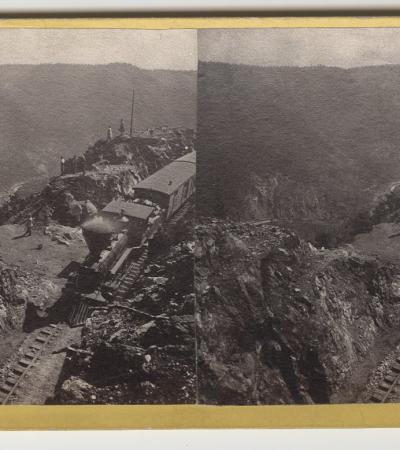

Scenes in the Sierra Nevada Mountains (Central Pacific Railroad, California/Nevada) by Alfred A. Hart

Alfred A. Hart, born in Norwich, Connecticut on March 16, 1816, was the principal photographer for the Central Pacific Railroad during the construction of the Overland Route. He photographed the construction from 1865 to 1869 when the last spike was driven by Leland Stanford at Promontory, Utah on May 10, 1869.

Home of John S. and Frances Jennings Casement, ca. 1870

Western Reserve agriculturalist Charles Clement Jennings built the Casement House, also known as the "Jennings Place," for his daughter Frances Jennings Casement in 1870. Designed by Charles W. Heard, son-in-law and student of Western Reserve master builder Jonathan Goldsmith, it was built in the Italianate style and featured ornate black walnut woodwork, elaborate ceiling frescoes, and an innovative ventilation system.

Tribute to Daniel T. Casement upon his death on December 14, 1881

The notice not only describe Dan Casement's life (1835-1881) but that of his business relationship with his brother Jack Casement. Also described is a near-death experience that occurred to Dan just before the Union Pacific railroad completion. Dan Casement left behind a wife, Mary, and three children.

Tribute to John S. Casement upon his death on December 13, 1909

A tribute that appeared on December 17, 1909, in The Painesville Telegraph. He had suffered ill health since he and his wife had visited San Jose, California, in April 1906 when a massive earthquake shook nearby San Francisco. He was pinned to his bed and suffered three broken ribs when parts of the hotel collapsed.

"Mrs. J. S. Casement," a reprint from The Painesville Telegraph

A biographical tribute to Frances Jennings Casement upon her death on August 24, 1928.