In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railroad Act, which chartered the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific Railroad Companies. Their task was to build a transcontinental railroad that would link the United States from East to West. Over the next seven years, the two companies raced toward each other from Sacramento, California on the one side to Omaha, Nebraska on the other, struggling through many obstacles and risks before they met at Promontory, Utah, on May 10, 1869.

The idea for a transcontinental railroad first appeared in a pamphlet in 1832. However, it wasn’t until 1848, when the United States annexed California as part of the Mexican Cession and discovered gold near Sacramento, that building the transcontinental railroad became necessary. During that time, thousands of hopeful miners made the months-long arduous journey to California by wagon on the overland trails or by ship around the tip of South America. Despite the obstacles, by 1850, the population had soared to the point that California was granted statehood. For these reasons, a dependable transportation connection was needed between the new state and the rest of the country.

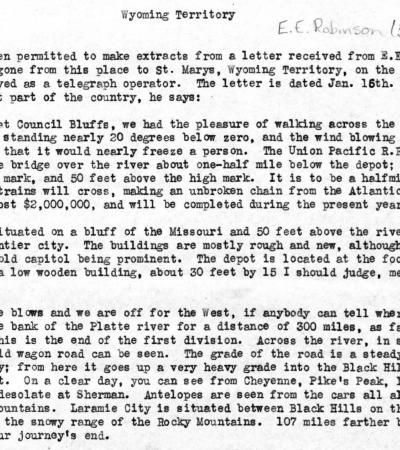

The federal government surveyed several possible rail routes through the West during the 1850s. Although it was established early that the route would go through Nebraska and cross Dakota Territory (now Wyoming), the U.S. Congress debated where the eastern terminus of the railroad should be—in a southern or northern city. Southern routes were objectionable to northern politicians, and northern routes were objectionable to southern politicians. Once the Civil War began in 1861, there was no longer any doubt. The route would have its terminus in a northern city.

As part of his presidential campaign platform, Abraham Lincoln promised that he would build the railroad if elected. True to his word, on July 1, 1862, and again in 1864, he signed the Pacific Railroad Acts. The acts provided construction by two government-subsidized companies, the Central Pacific starting from Sacramento on the west coast across the Sierra Nevada Mountains to the east and the Union Pacific Railroad starting from Omaha-Council Bluffs west over the Rocky Mountains. The acts also provided grants of land based on the mileage of track laid and they provided low-interest loans based on the difficulty of terrain that construction crews had to cross.

The Central Pacific construction was well underway before the Union Pacific work got started. Many (primarily Chinese) workers were already laboring away on the Central Pacific while Union Pacific bosses were searching for workhands. Finally, construction began on Dec. 2, 1863, on the Union Pacific in Omaha, Nebraska Territory. Due to difficulties in obtaining financial backing and the unavailability of workers and materials due to the Civil War, the UP tracks only made 40 miles by the end of 1865. However, construction progressed the following year, as new waves of Irish immigrants and a vast influx of Civil War veterans showed up pursuing paid work.

The massive railroad construction project required an entire support network, including medical staff, cooks, and proprietors of provisions, stores, and living areas. Tracklaying contractors for the UP branch were Union General John S. “Jack” Casement and his brother Dan Casement. Jack was the track-laying boss, and Dan handled the financial affairs. The lead financier and general manager of the Union Pacific was Thomas Durant. The chief engineer was General Grenville Dodge, and the superintendent of construction was Samuel B. Reed. Sidney Dillon was one of the principal contractors and was invaluable to the project due to his vast experience in railroad building.

Several phases were necessary for the construction of the railroad. First came the survey crews who selected the course. Next came the graders who leveled the route. Then there were the bridge builders and tunnelers. The surveyors, graders, and bridge builders were usually many miles apart and faced isolation, supply issues, bad weather, and other problems. Once the roadbed was ready, the construction crews arrived. Coordination with the many suppliers was a constant irritation as ties cut in the mountains, rails shipped from eastern foundries, food from hunters and eastern growers, grain for the thousands of animals used in the effort, and a constant workforce all needed to be at the “end of track” at the same time if track laying was to take place. Nearly ten thousand people worked at the same time when construction was taking place on the transcontinental railroad line.

The labor was back-straining for days on end, for not necessarily high wages and in sometimes brutal conditions that included harsh weather, accidental explosions, and snow and rock avalanches. The diet was a tedious fare mainly consisting of beef and bread and coffee. Close quarters within the work camps made for unsanitary conditions. Water-borne illnesses were rampant.

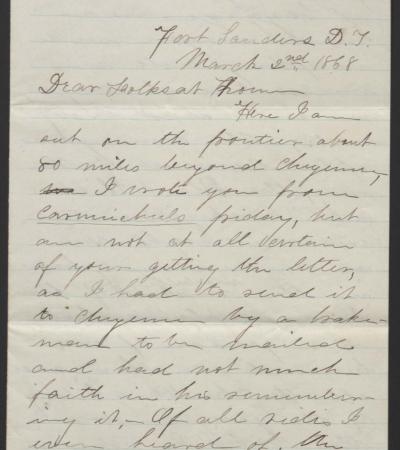

Other risks to the workers included attacks by Native American tribes. The railroad undermined the sovereignty of Native nations and threatened to destroy indigenous communities as the route expanded into territories they inhabited. The federal government ordered the United States Army to have soldiers travel with the construction crews for protection. Forts, such as D.A. Russell near Cheyenne, Sanders near Laramie, and Steele outside of Rawlins were built along the right of way. However, not all Native American tribes responded the same to the railroad. The Pawnee people formed a strong alliance with the U.S. Army to defend the railroad against the Pawnee’s traditional Indian enemies. Led by Major Frank North, a uniformed battalion of 800 Pawnee men patrolled the railroad to protect crews and livestock from Sioux and Cheyenne raiders. The allied Oglala Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Southern Arapaho tribes, already struggling with the loss of natural resources due to rapid Euro-American settlement and weary of broken U.S. treaties, made regular attacks on construction workers and the railroad line.

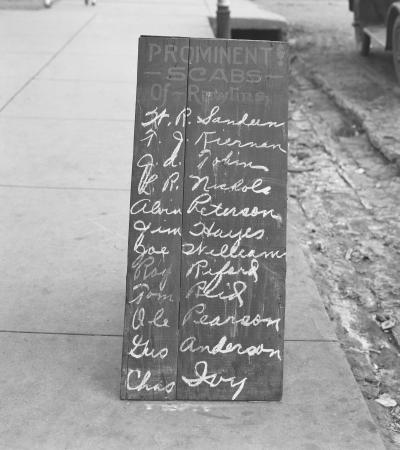

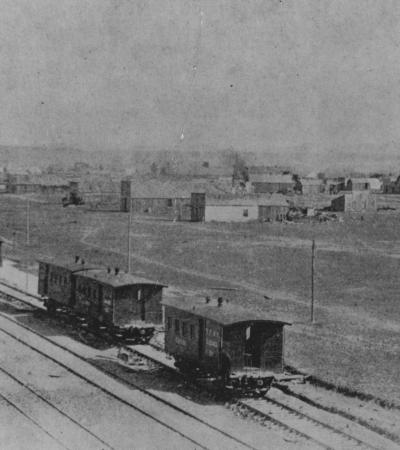

Another complication was the hundreds, sometimes thousands, of people called “track-followers.” Among these people were gamblers, card sharks, saloon keepers, prostitutes, thieves, and others who prospered from Union Pacific laborers. These people traveled with the railroad, setting up tents or tar-paper shacks in small communities termed “Hell on Wheels” moving them ever westward as the tracks advanced. Some of these “ends of track” towns remained to become permanent cities. In Wyoming, Laramie, Rawlins, Rock Springs, Green River, and Evanston started as tent cities. Because they became important as stations on the railroad or because they were close to minerals, they remain as important cities today.

Still another threat to the railroad happened from within. Union Pacific executives George Francis Train and Thomas C. Durant founded a fraudulent company, Crédit Mobilier of America, to greatly inflate construction costs. Basically, how the scheme worked was that Union Pacific contracted with Crédit Mobilier to build the railroad at rates greatly above cost. The inflated construction contracts brought great profits, which were divided between Durant, Train, and other shareholders of Crédit Mobilier. The railroad cost $50 million to build, but Crédit Mobilier billed $94 million with UP executives pocketing the additional funds. Part of the excess cash was used to bribe several Washington officials, including U.S. Representative Oakes Ames, for laws, funding, and regulatory rulings favorable to the Union Pacific. Their action nearly bankrupted Union Pacific. After a disagreement with Rep. Ames, one of the shareholders, Henry Simpson McComb, leaked compromising letters to the New York Sun newspaper. The Sun broke the story on September 4, 1872, which led to a congressional investigation as well as a Department of Justice investigation. High ranking U.S. officials were implicated, causing great public distrust of Congress and the federal government.

Although men dominated railroad construction, women were involved in a number of ways including as entertainers and hotel and newspaper operators, as well as wives of railroad employees. Their stories are more difficult to find since their participation was deemed of lesser importance. Because of the intensive physical labor, women did not generally labor on the actual construction. Most visibly, women in the Union Pacific end-of-track town fulfilled the desire of railroad crews for entertainment and sex. However, women also offered domestic support, such as cooking, laundering, sewing, and general camp maintenance. Other women worked with their husbands or families running boarding houses or printing newspapers. The wives of railroad crews offered emotional support. A helpful article on this topic is “Women and the Transcontinental Railroad through Utah, 1868-1869” by Wendy Simmons Johnson that appeared in Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol. 88, No. 4 (Fall 2020).

Track laying continued across Wyoming during the summer and fall of 1868, finally entering Utah in December. After a short break during the winter, construction resumed, culminating in completing the transcontinental railroad at Promontory Point, Utah Territory, on May 10, 1869. The golden spike was driven, and the connection between California and the country was complete.