Immigration has shaped the identity of the United States from its founding to the present day.

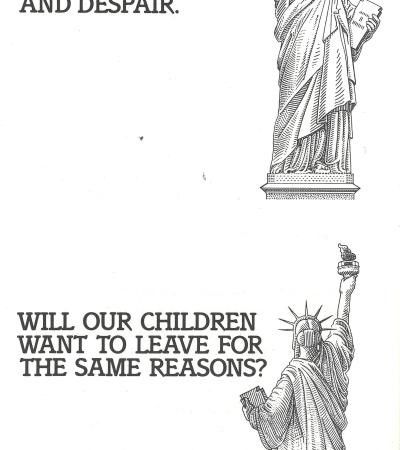

The reasons people leave their home countries—poverty, war, famine, violence, or political persecution—continue to drive migration patterns. For more than 200 years, immigrants have arrived in America seeking freedom and opportunity. But this journey is often difficult. In fact, the history of immigration is filled with stories of welcome and rejection, hard labor and hope, legal reforms and setbacks. Wyoming’s own immigrant history closely reflects the national narrative, from major contributions to local industries to laws that either helped or harmed immigrants.

Between 1820 and 1880, the majority of immigrants to the U.S. came from countries like Germany, Ireland, and Great Britain. Many of these early arrivals were seeking to escape hardship, such as the Irish Potato Famine of the 1840s. During this period, immigration laws were minimal. In fact, before 1875, anyone could enter the U.S. However, exclusion laws soon began to take shape, banning people like convicts and prostitutes. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred Chinese laborers from immigrating. It was the first U.S. law to ban immigration based on nationality and set a harsh precedent for the future.

Wyoming's history is full of immigrant contributions. European immigrants worked for the Union Pacific Railroad and helped settle towns across the state. Chinese immigrants worked in coal mines and opened stores and restaurants. Hispanic immigrants played a crucial role in the sugar beet industry, especially in places like Torrington and Wheatland. Basque sheepherders came from Spain in to work in Wyoming’s rugged landscapes, contributing to the sheep ranching economy.

Perhaps the biggest numerical swell in the immigrant population in Wyoming occurred at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center, where more than 14,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II. Though many were already U.S. citizens, their Japanese ancestry made them targets of suspicion and racism. Their treatment highlights a moment when fear and prejudice overpowered justice and civil rights.

Wyoming politicians have also had a hand in shaping immigration policy. Throughout the 20th century, they responded to letters from constituents asking for help obtaining visas for relatives. Some voters wrote in support of refugee policies. Others wrote fearfully that immigrants would “steal jobs.” Local leaders participated in broader national immigration debates and decision-making.

As immigration increased, so did efforts to “Americanize” newcomers. From the 1910s through the 1920s, the Bureau of Naturalization led a nationwide Americanization campaign. In Wyoming, including in cities like Laramie, immigrants were encouraged to attend free English and citizenship classes. The goal was to help immigrants better understand American history, government, and culture—while preparing them for naturalization.

Citizenship wasn't just about learning English; it was about being accepted and included. But this period also reflected a belief that immigrants had to leave behind their old ways to be considered “truly American.” Some believed that keeping one’s native language or culture slowed down Americanization, though others argued it added to the richness of American society.

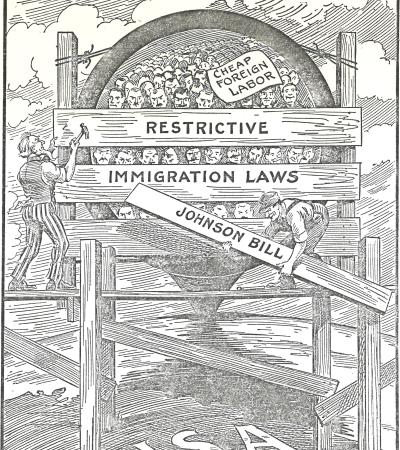

The story of immigration continued to evolve through the 20th century. In 1924, the U.S. Border Patrol was created, and quotas were established that limited immigration from many countries. Refugees from World War II and later conflicts like Korea and Vietnam were eventually admitted under special programs. Still, immigrants from Asia, Latin America, and other non-European regions faced many legal barriers.

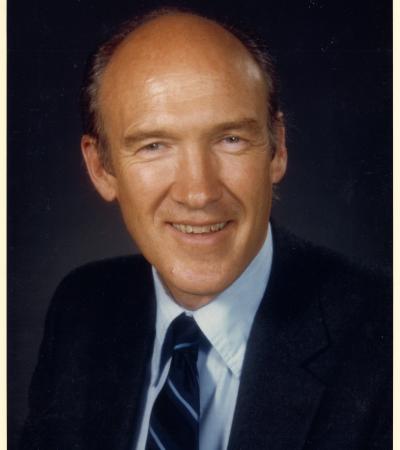

In 1986, the U.S. passed a major immigration law: the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA). It aimed to reduce illegal immigration by penalizing employers who knowingly hired undocumented workers, while also offering a path to legal status for immigrants who had been in the country for years. One of the leading architects of this legislation was Wyoming’s own Senator Alan K. Simpson. Working with Representative Romano Mazzoli of Kentucky, Simpson helped write and pass this bipartisan reform law. The law also introduced new visas, like the H-2A for agricultural workers and the H-2B for non-agricultural temporary labor.

Though IRCA showed a serious attempt to solve immigration challenges, it didn’t fix everything. Border crossings, particularly at the southern U.S. border, continued, and the debate over how to balance security, labor needs, and human rights is still ongoing. Today, immigration policy is debated in Congress and implemented by agencies like U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), both part of the Department of Homeland Security.

From railroad workers and sugar beet laborers to refugee families and visa-seekers, immigrants have shaped Wyoming just as they have shaped the nation. Immigration in Wyoming includes stories of welcome and work, but also exclusion and injustice. From the Chinese Exclusion Act to the internment of Japanese Americans to Senator Simpson’s efforts at reform, Wyoming’s immigration history tells the broader story of America. By learning about these past events, students and citizens alike can better understand current immigration debates and the people behind them. After all, immigration isn’t just a policy issue—it’s a human one.