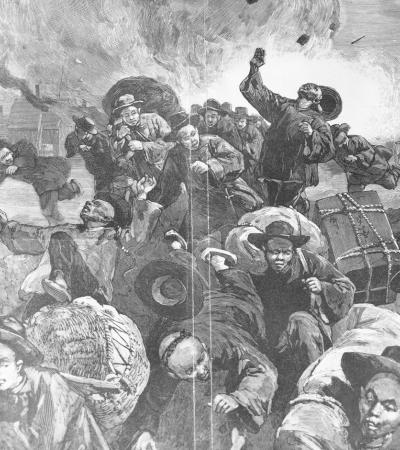

On Sept. 2, 1885, white coal miners in Rock Springs, Wyoming Territory attacked Chinatown, the part of town where Chinese coal miners lived. Although hundreds of Chinese escaped, the white rioters killed 28 people while burning and looting the houses and shops. All the miners worked at mines owned by the Union Pacific Railroad.

What drove the white miners to commit this kind of violence? What, if anything, had the Chinese done to anger them?

The Chinese had been in America at least since the 1849 California Gold Rush. They accepted lower wages in comparison with what the white miners would accept. This drove wages down for everyone and white workers resented it. In the early 1870s, white workers in San Francisco and Los Angeles threatened the Chinese workers and, in Los Angeles, white people killed 23 Chinese laborers. No charges were ever brought against the murderers.

During the construction of the transcontinental railroad, large numbers of Chinese laborers worked for the Central Pacific Railroad building it from California in the west eastward to meet the rails of the Union Pacific in Utah in 1869. Later, many of the Chinese in Wyoming worked at the Union Pacific mines in railroad towns such as Rock Springs, Evanston, and others. During the 1870s, strikes by white miners in Wyoming caused the company to hire more Chinese miners, which only increased the white miners’ resentment as the company was playing the different groups of miners against each other.

On the day of the attack in 1885, the Sweetwater County sheriff learned of the violence about an hour after it began. He took a special train to Rock Springs but could not find anyone to join him in a posse.

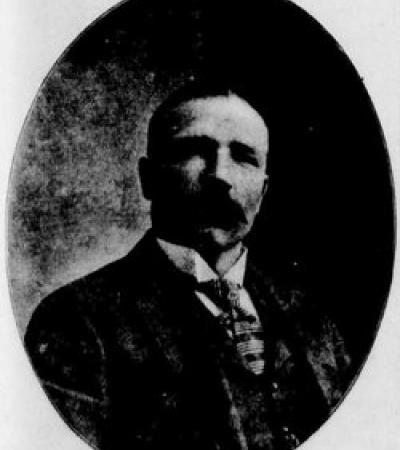

Territorial Governor Francis E. Warren traveled to Rock Springs. To demonstrate that he was unafraid and to help calm the white miners, he left his railroad car several times and made a show of walking back and forth on the depot platform.

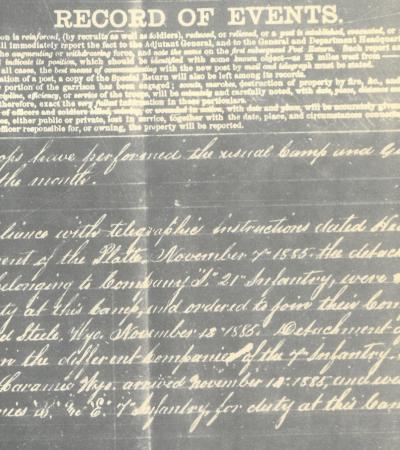

Warren also telegraphed President Grover Cleveland asking for troops to restore order since Wyoming had no territorial militia. At his suggestion, the company sent a slow train the 15 miles from Rock Springs to Green River to rescue the scattered Chinese and give them food, water, and blankets. Meanwhile, the Uinta County sheriff in Evanston grew nervous about the situation in his area, too. Warren could do nothing but travel to Evanston to calm matters.

By this time, most of the Chinese were eager to get out of Wyoming; most from Rock Springs had ended up in Evanston after the violence. Their leader, Ah Say, asked the Union Pacific for railroad tickets and for the two months’ back pay the company owed them. The company refused both requests.

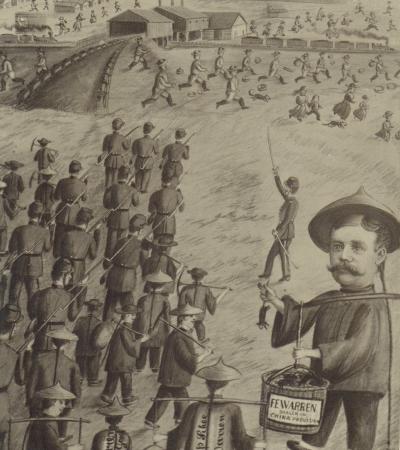

Nearly a week after the killings, troops arrived in Rock Springs and Evanston. Company guards escorted about 600 Chinese, then in Evanston, into boxcars supposedly bound for San Francisco. It wasn’t true; the train steamed to Rock Springs, with Warren and top company officials in a car at the back.

Back in Rock Springs, the company still refused the Chinese any passes to California or back pay. White miners continued to harass them. The company refused to sell them food, threatened evict them from their temporary boxcar homes, and finally threatened to fire and blacklist any Chinese who had not returned to work by Sept. 21. About 60 Chinese left; the rest returned to work.

Sixteen white miners were arrested for the riot, destruction, and murders, but none were ever charged because no witnesses were willing to testify. The official casualty count was 28 Chinese killed, 15 wounded, and all 79 of the Chinatown buildings looted and burned.

Governor Warren’s role in this debacle was mixed. Although he succeeded in calming the atmosphere, thus preventing further violence, he helped trick the Chinese into returning to Rock Springs and he refused to intervene in the matter of their back pay.

Ultimately, the Union Pacific Company got what it wanted: continuing low pay for all miners—and an ongoing supply of coal for its trains.